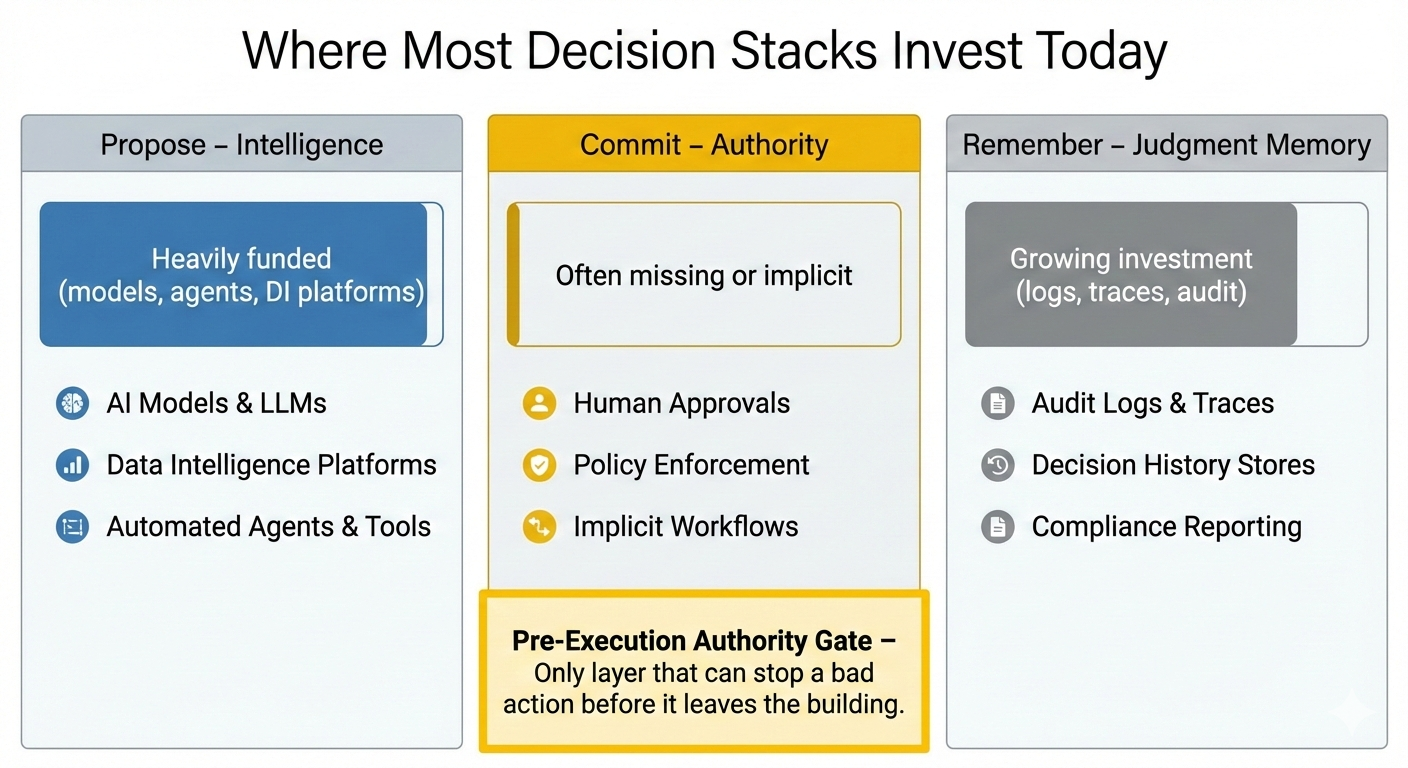

Decision Intelligence Has 3 Layers. Most Stacks Only Govern Two.

Everyone’s talking about Decision Intelligence like it’s one thing.

It isn’t.

If you collapse everything into a single “decision system,” you end up buying the wrong tools, over-promising what they can do, and still getting surprised when something irreversible goes out under your name.

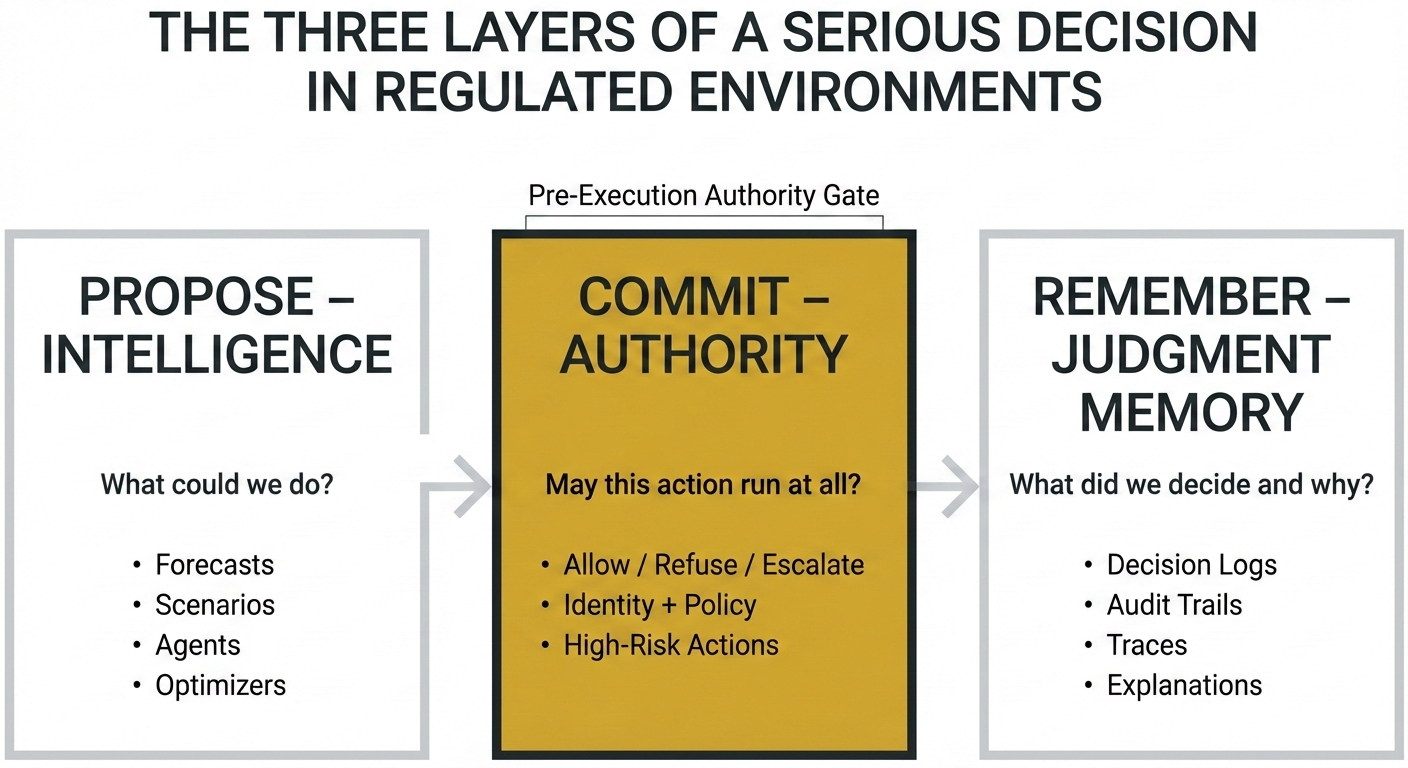

In any serious environment—law, finance, healthcare, government, critical infrastructure—a “decision” actually has three very different jobs:

- Propose – intelligence: “What could we do?”

- Commit – authority: “Are we allowed to do this at all?”

- Remember – judgment memory: “What did we decide, why, and can we show our work?”

Most of the market is investing heavily in #1 and #3.

Almost nobody clearly owns #2.

That missing middle layer—the pre-execution authority gate—is where the highest risk actually lives.

This article is about naming those three layers clearly, showing how they fit together, and explaining why we chose to specialize in the Commit layer for high-risk legal actions.

Layer 1 – PROPOSE

Intelligence: “Given what we know, what could we do?”

This is where almost all “decision intelligence” platforms and AI tooling live today.

The job of this layer is to propose options:

- Build forecasts, simulations, and scenarios

- Run optimizers to suggest “best” choices under certain constraints

- Use LLMs, RAG, and agents to surface patterns, risks, and trade-offs

- Generate ranked recommendations: option A vs B vs C

In this layer you see:

- Decision intelligence platforms

- Causal AI tooling

- Optimization engines

- BI + analytics that are finally trying to be more prescriptive than descriptive

All of that is valuable. It’s what turns raw data into structured proposals.

But proposals are not decisions.

They answer:

“What could we do, given this information and these assumptions?”

They do not answer:

“Who is actually allowed to commit this action, here, now, under our rules and obligations?”

That’s a different job entirely.

Layer 3 – REMEMBER

Judgment Memory: “What did we decide, why, and can we show our work?”

I’m jumping to Layer 3 next on purpose, because this is the second place most organizations are now investing.

Once a decision is made (or a recommendation is accepted), someone will eventually ask:

- “Why did we do that?”

- “Who signed off?”

- “What assumptions did we make?”

- “What did we know at the time?”

In regulated environments, that’s not curiosity—that’s survival.

The Remember layer is everything that lets you replay judgment later with evidence, not just stories:

- Decision logs and rationales

- Causal traces and influence diagrams

- Audit-grade operational memory

- Versioned policies and models linked to specific decisions

- The ability to reconstruct: “At this time, with this information, this person/system approved this action for these reasons.”

Good decision-intelligence platforms are starting to make progress here: better lineage, explanations, dashboards, and traces.

But again, notice the timing:

This layer captures and explains what already happened.

It can make you more accountable.

It can help you learn.

It can help you defend yourself in front of a regulator or board.

It cannot stop a bad action from executing in the first place.

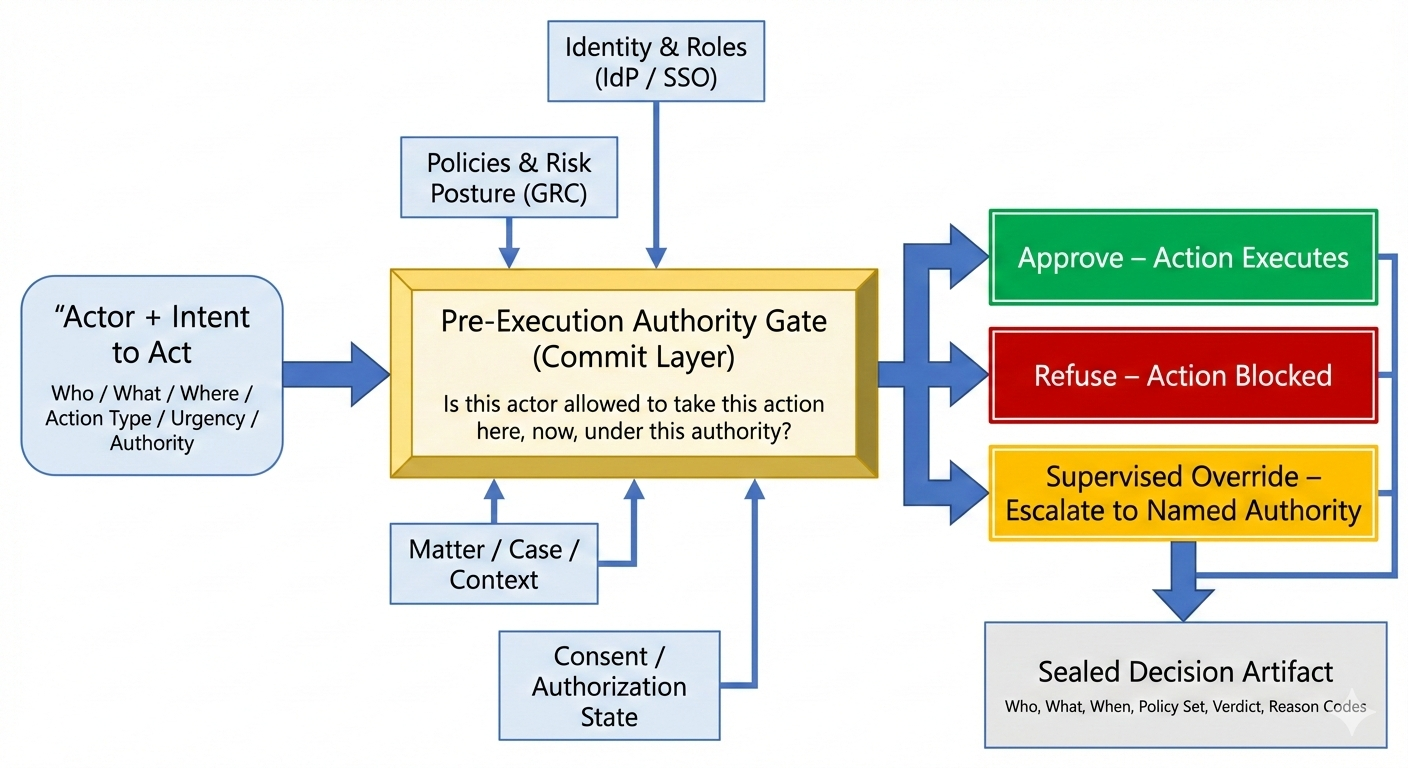

Layer 2 – COMMIT

Authority: “May this action run at all?”

This is the layer almost nobody names cleanly, and it’s the one regulators, boards, and malpractice insurers keep circling in different language.

The Commit layer only has one job:

For this specific actor, taking this specific action, in this context, under this authority — may it run at all: allow, refuse, or supervised?

Not “what seems optimal.”

Not “how confident is the model.”

Not “does the causal graph look sensible.”

Just: may this action execute under our name, yes/no/escalate — and where is the evidence?

Structurally, this layer looks very different from the other two:

- It sits in front of high-risk actions:

- file / send / sign

- approve / move money / commit a change

- It is wired to identity, roles, and org structure (IdP/SSO).

- It consumes policy and risk posture from GRC / policy systems.

- It understands matter / case / client / venue context in domains like law.

- It returns a binary (or ternary) verdict:

- Approve – the action may proceed

- Refuse – the action is blocked

- Supervised override – allowed only under an explicit supervisory regime

And—crucially for regulated work—it leaves behind an artifact that can stand up to external scrutiny:

- Who attempted the action

- What they tried to do

- Under which identity / role / matter / venue

- Which policy regime was applied

- What the verdict was (approve / refuse / supervised)

- High-level reason codes

- Timestamps and integrity protections

That artifact is not a log line. It’s evidence.

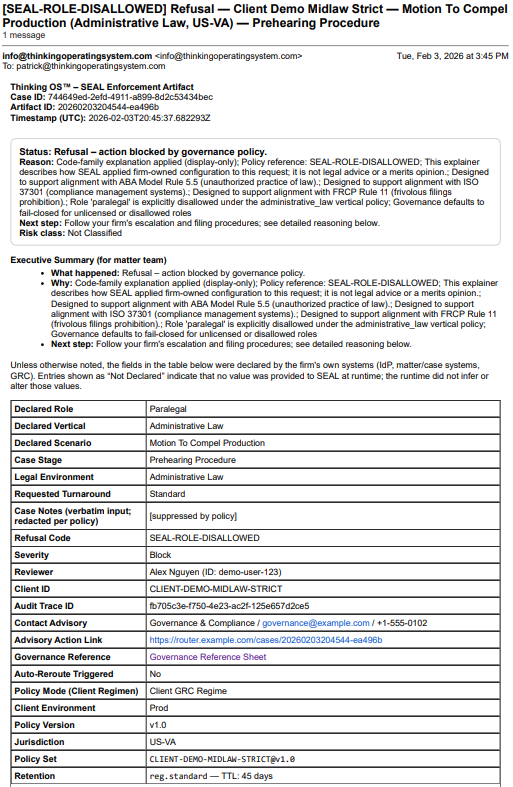

In our world (law), this is exactly what SEAL Legal Runtime does:

A sealed pre-execution authority gate in front of high-risk legal actions (file, send, approve, move) that answers the commit question and emits sealed, tenant-owned decision artifacts for every approve / refuse / supervised override.

We call the discipline Action Governance and the category Refusal Infrastructure for Legal AI.

But the structural pattern generalizes.

How the Three Layers Fit Together

Once you separate these layers, a lot of confusion in the “decision intelligence” conversation disappears.

1️⃣ Propose – Intelligence

- Goal: expand the option set, quantify trade-offs

- Tools: DI platforms, causal engines, optimization, LLM agents

- Output: “Here are the options and their projected impacts”

2️⃣ Commit – Authority (Pre-Execution Gate)

- Goal: decide whether a specific action is allowed to execute at all

- Tools: pre-execution authority gate, wired to IAM + GRC + domain context

- Output: allow / refuse / supervised + sealed artifact

3️⃣ Remember – Judgment Memory

- Goal: replay and audit decisions over time

- Tools: logs, decision records, traces, explanation layers, archives

- Output: “Here is what we did, and why, at that time”

They are not interchangeable.

- You can have brilliant proposals and rich judgment memory—and still let an action run that no one ever had the authority to commit.

- You can have strong authority gates but poor memory—and struggle to prove to a regulator what you did and why.

- You can have meticulous memory and authority, but weak proposal intelligence—and simply fail to see better options.

You need all three.

But only one can prevent harm before it hits the real world.

What Goes Wrong When Commit Is Missing

You can see the missing middle layer in most AI “incidents” today:

- A system generates a persuasive recommendation.

- A human or downstream workflow treats it as effectively binding.

- No one can later answer:

- “Who actually had the right to let this happen?”

- “What authority did they rely on?”

- “Where is the record that shows that call?”

A few common failure modes:

1. Proposals Quietly Become Commitments

Recommendation systems, DI platforms, and agents were designed to suggest.

In practice, people wire them into workflows where:

- “Recommend and notify” slowly becomes “recommend and auto-apply above a threshold.”

- UI labels say “suggested,” but operations treat them as the default.

- Over time, “the system usually does this” becomes “that’s how we do it.”

Without a distinct Commit layer, there is no clear:

- decision owner

- authority check

- evidentiary record of the yes/no

- escalation path when something feels off

2. Governance Lives on Slides, Not at the Gate

Boards and risk committees approve:

- AI policies

- risk appetite statements

- decision forums

- escalation protocols

All of that matters.

But if none of it is wired into a pre-execution authority gate, then at runtime the real rule is:

“If the tool allows it and no one intervenes, it goes.”

From a regulator’s perspective, that’s governance in name only.

3. Auditors Are Forced Into Archaeology

Months later, when someone asks “how did this get approved?”:

- DI platforms export traces.

- Email threads get searched.

- People try to reconstruct who clicked what.

That’s archaeology, not judgment memory.

A clean Commit layer would instead give them a single, sealed verdict per action:

“On this date, under this policy version, this actor was (or was not) authorized to execute this action. Here is the artifact that proves it.”

Why We Chose to Specialize in the Commit Layer

We operate in law first, because it’s one of the hardest proving grounds:

- Identity and authority are tightly regulated.

- Actions like filing, sending, or binding a client are irreversible once they leave the firm.

- Professional responsibility, malpractice, and regulatory regimes require provable authority—not just “we had good tooling.”

In that world, the question we kept coming back to was brutally simple:

“Who was allowed to let this action hit the real world?”

Everything else—model quality, decision intelligence, analytics—sits upstream or downstream of that question.

So we built SEAL Legal Runtime as:

A sealed pre-execution authority gate for high-risk legal actions, wired into firms’ own identity and GRC systems, that returns approve / refuse / supervised override and produces sealed, client-owned artifacts for every governed decision.

We don’t govern prompts.

We don’t inspect full matter content.

We don’t claim to control every agent everywhere.

We govern a bounded, high-risk surface (file / send / approve / move) in wired legal workflows, and we leave behind evidence.

In the broader decision-intelligence landscape, that’s one very specific job:

- We are not the platform that proposes the best legal strategy.

- We are not the system of record for every business decision.

- We are the authority gate that answers: “May this legal action proceed at all, under our rules?”

And we think every regulated domain will eventually need its own version of that layer.

How to Use This Framework in Your Own Stack

If you’re a GC, CISO, CDAO, or decision-intelligence lead, you can use this three-layer frame as a quick diagnostic.

For any important decision class (claims, trades, filings, orders, payments):

#1. Propose – Intelligence

- What systems propose options?

- How do they model trade-offs and uncertainty?

- How do humans interact with their recommendations?

#2. Commit – Authority

- Who (human or system) has the right to say yes to the action?

- Where is that encoded—in org charts, policies, or an actual gate in front of the action?

- Can an action execute without a clear allow/refuse/escalate verdict?

- Is that verdict recorded as evidence, or just implied?

#3. Remember – Judgment Memory

- If you had to explain this decision six months from now, what would you show?

- Are you relying on logs and emails, or structured decision records?

- Can you tie a concrete action back to: who, what, under which authority, and why?

If you can’t point to a distinct Commit layer for your highest-risk actions, you’ve just found your largest blind spot.

The Takeaway

Decision Intelligence is not one thing.

- Layer 1 – Propose gives you smarter options.

- Layer 2 – Commit governs what may actually run under your name.

- Layer 3 – Remember lets you replay and defend judgment over time.

Most organizations are pouring effort into #1 and #3.

The next wave of scrutiny—from boards, regulators, and insurers—is going to land squarely on #2:

“Who actually had the authority to let this action execute, and where is the record that proves it?”

If you can answer that cleanly, the rest of your decision-intelligence investments become far more credible.

If you can’t, all the proposals and traces in the world won’t save you the day after a bad decision leaves the building.

That’s why we’re betting on the Commit layer first—starting in law—and why I think every serious AI stack will eventually have to do the same.